Unconditional support, trust, respect, generosity, and courage are the behavioural values required for agile—and also for rugby. On the surface, the software development methodology and the rough team sport may seem to have little in common. But Luis Novella writes that rugby can actually teach you a lot about agile.

When I recently joined an agile team, I suddenly realised I had actually been implementing agile for a few years, just without leveraging the branding. It wasn’t until I listened to Johanna Rothman speak that it dawned on me: Not all things called agile are truly agile, and there are a lot of practices that are agile but are not categorised as such.

Once I understood what agile really means, I realised that I’d seen many of its central tenets contained in another system that’s important to me. Unconditional support, trust, respect, generosity, and courage are the behavioural values required for agile—and also for rugby. On the surface, the software development methodology and the rough team sport may seem to have little in common, but in this article, I’ll show you that agile and the sport of rugby are alike where it really counts—and understanding how to be a team player can improve your career as well as your game.

Trust in Your Teammates

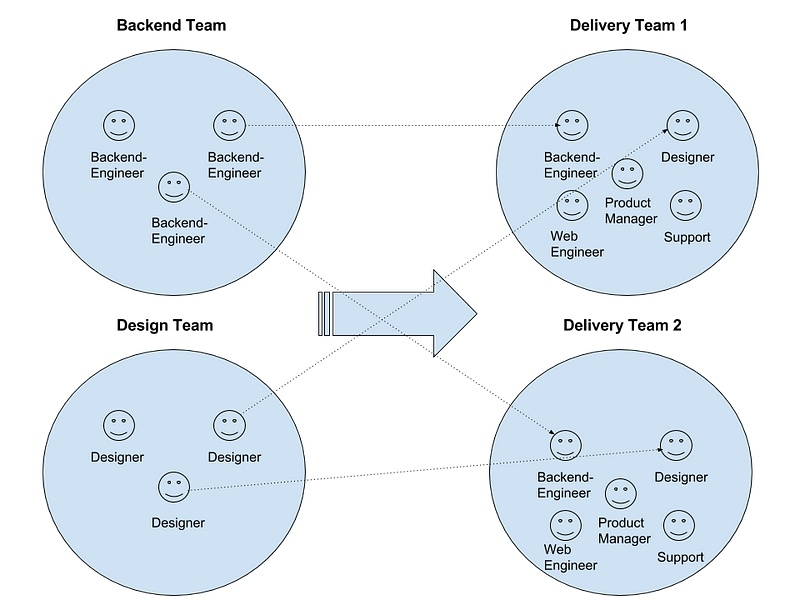

Rugby teaches you to find the most optimal, collectively intelligent strategy within a group of diverse and versatile individuals. When everyone has this mindset, you get sustainability, innovation, and the pleasure of working with a team fully engaged toward a common goal. Overall, rugby is a decision-making game that focuses on shared leadership, and many types of it. It assumes that individuals will be specialists for certain tasks, but they will have the contextual intelligence to make the best decisions for the team based on a deep sense of self-awareness and consciousness of the other team members and the progression toward the goal. Sound familiar?

Despite having played a few rugby games here and there when I was younger, I never imagined the endurance of the behavioral blueprint the sport could generate in a high-performance team. I would argue that the training provided by rugby in terms of behavior is useful regardless of what agile technique or method best fits the particular challenge.

One of the key elements is trust and unconditional support between team members. Despite 160 years of updates, improvements, and new laws, rugby teams at any level still function the same way: When the player with the ball makes a decision, every single teammate actively supports and engages with his position and the context, aiming to provide the best options for the ball carrier (who is always the boss in rugby, if you are into the boss concept). Every player trusts that the decision-maker will make the best choice based on his vantage point, opposition, position on the field, and available support. Once a decision is made, everyone on the team makes the maximum effort for the result of that decision to accomplish the best outcome for the team.

The decision-maker also trusts that everyone behind him will be attentive and available. He believes that if his execution fails, no one will recriminate him; instead, he will be supported. In rugby, you inevitably “fail fast” and make plenty of decisions that turn out to be negative, but you know your innovation was encouraged and respected by the team. Your team trusts that you did the very best you can. They also trust that you have trained and prepared yourself to have been in the best possible condition to play.

Trust releases many opportunities in life. You can innovate and create. You can surprise the opposition. You can discover abilities in your teammates that you did not know were present.

I have had the advantage of working with business leaders who have the courage required to embark in agile transformations the right way—to really and truly happen, change has to start at the top, and the first one to change has to be the inspiration leader. In my opinion, this trust and ability to innovate and err generates pleasure in what we do. It makes our work open and helps us measure and get feedback, because you also trust that the people around you want to make you better.

Just like rugby, agile is a learning system in constant change played by a collectively intelligent team, and the team’s every move is enabled by trust.

By: Luis Novella from the Spark Team

https://www.agileconnection.com/article/what-rugby-can-teach-you-about-trust-agile-teams?page=0%2C1