Rejecting roles: That’s marketing’s job. You need to talk to IT.

Having roles is considered essential by most organisations. We’ve read dozens of business blogs, HR advice articles and even management training courses that insist clearly defined roles lead to better results, greater productivity and higher motivation. Without clear definition of roles, they warn that tasks get missed, no-one takes responsibility, the office is chaotic and individual motivation drops.

We disagree.

The writers of this advice have grasped the outcomes they want – people taking pride in their work, everyone focusing on delivering value, individuals coordinating and collaborating – but they’ve applied the wrong solution.

They’ve confused roles with responsibilities.

That may not sound like a big deal, but we think it is. Rigid role definition has some major downsides. We believe it hurts companies and individuals, costing them in creativity and happiness.

Most organisations intend their role definitions to be a way of signalling particular specialisations, expertise and responsibilities… but instead, the definitions swiftly harden into barriers, marking out territory which is defended against ‘interference’ from others. Have you ever been told to back off by the marketing manager for commenting on the new advert? Been refused access to the code base by the developers, ‘in case you break something’? Been told to leave presentations to ‘the sales guys’ or forecasts ‘the finance guys’? At the extreme, you may have your opinion rejected with a straight-forward ‘well it’s not your job to worry about x, it’s mine!’.

Individuals may also use their role definition as a way of avoiding unpleasant or boring tasks. This ‘that’s not in my job description’ approach ends up making the company less efficient as well as eroding team motivation. I remember organising a last-minute marketing stunt when I worked at Unilever. I was booking a double-decker bus to turn up and I wanted to check it would actually fit into the office forecourt. The marketing assistant nipped down to Reception to check. An hour later, she returned. The security guard had refused to measure the gateway and if it was beneath the dignity of a security guard, then she reckoned it was beneath the dignity of a marketing assistant as well. So I borrowed the security man’s tape-measure and checked the gateway (you could – quite literally – have fitted a bus through there). Anything wrong with doing my own measuring? Absolutely not. Anything wrong with wasting an hour of time arguing about whose job it was? Plenty.

Roles are comfortable – but bad for us

It’s very human to defend our own work and our own opinion. When we can dress this up with the authority of experience, expertise and organisational separation – all the better. Except it isn’t. Rigid role definition acts as a barrier and can stifle innovation. It can also make things slower and less efficient.

If a customer rings up with a problem, they want a solution, not to be told that only part of their problem can be dealt with by this department, and they must be passed on to billing or whoever to deal with the rest of it.

It’s not great for individuals either. Sticking to just one thing may mean our knowledge gets deeper, but also narrower. We can get bored or worse, so convinced of our own expertise that we can’t take on other points of view.

Being Radical: Sticking to the start up way

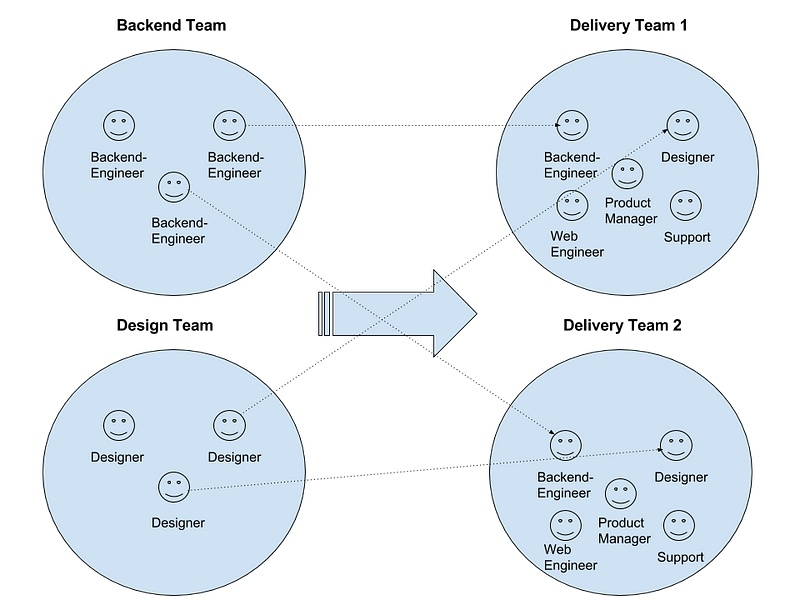

In many start ups, a lack of defined roles is the default position. There is not enough money to hire specialists – instead developers must learn to present to investors, marketing managers must be able to create and manage their own customer data, and everyone must have a grip on the financial assumptions as well as a grasp of the their product (this often means some grasp of the technology).

When entrepreneurs look back on the early stage of their companies, they often comment on wistfully on the diversity of work and of how close to the customer it meant they were.

Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, recalled being the ‘mailroom grunt’ in the company’s early days, driving books to shipping and courier companies in his 1987 Blazer. But this doesn’t scale, right? Jeff Bezos is not still doing deliveries. Actually, he is. He spends a week every year in the warehouse. It’s not a PR gimmick, because he refuses to set up interviews when doing it. It’s an opportunity to stay connected to his responsibility – leading Amazon – and not the role of CEO. That includes really understanding conditions for employees – something for which Amazon has received a lot of criticism – and staying close to core services like order fulfilment.

Another trick used at Amazon is to have individual employees who have no role at all. Bezos has ‘shadows’, people who simply follow him around. It means there’s always someone free to chase a wild idea or set up an experiment – and it recognises that a responsibility like ‘envision Amazon’s future’ requires several people, not just a single role.

So what should we do?

1. Responsibilities not roles

Some radical companies go for a very broad responsibility ‘provide value to the company’ and say that how this is fulfilled is up to the individual. Others go for more precise responsibilities: ‘help the customer’ or ‘make sure we comply with financial regulations’.

The point is that how you fulfil these needs can require doing tasks which, in other companies, would be seen as belonging to differing roles.

2. Trust people

A lack of roles makes people more responsible, not less. Tasks rarely get missed because everyone knows they have total responsibility for the work – no tester will come pick up the programmer’s bugs; no finance controller will correct over-optimistic projections.

3. Trust people some more

A lack of roles doesn’t mean that everyone will try to do everything. People naturally gravitate towards what they’re interested in and what they’re good at. If someone is convinced she’s a brilliant illustrator and everyone else insists the stick men cartoons are rubbish, she will soon stop.

4. Value dissent not consensus

No roles doesn’t mean you have to design by committee. Heated arguments are common, and that’s fine. Even if people don’t agree at the end of the debate, the important thing tends to be to air the problem. Opinions can be rejected; a decision can still be made, risks can still be taken…

By: Helen Walton from Gamevy